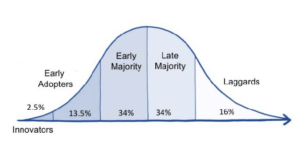

We “buy” the idea of change — newness — difference — when we’re ready. Whether it’s a new product or an idea, a tech advance, or a “novel” virus, each of us responds at different rates.

♦

How have you progressed along the pandemic curve? Have you heeded some/all of the advice from the “innovators” (“brave people, pulling the change”) such as Anthony Fauci, other scientists, and government officials who have led the way?

When and in what order did YOU start to…

- Keep social distance — 6 feet apart — in public?

- Wash hands more often?

- Refill prescriptions and order extra…just in case?

- Refrain from touching your face?

- Wipe down frequently-touched surfaces, like doorknobs and counters?

- Wear a mask in public?

- Wear gloves in public?

- Discard bags and disinfect groceries before bringing them into the house?

- Leave shoes at the front door and wipe them with disinfectant?

- Cancel plans that involved going somewhere public, like a restaurant or gym?

- Bar guests — even relatives and close friends — from your home?

- Immediately wash clothing worn outside?

- Stop touching elevator buttons, door handles, and other objects in public spaces?

- Stay at home except for gas, groceries, or medicine?

- Order food and other essentials online?

- Turn down paid work that required leaving home or visiting someone else’s home?

Whether you can tick off many or even all of the above depends on who you are, your circumstances, and who’s whispering in your ear.

Welcome to what I think of as “the new different.” There’s nothing “normal” about it. Hereafter, life will change in ways we can’t predict.

I am not among the early adopters — people who are “already aware of the need to change and so are very comfortable adopting new ideas.” To be honest, I did not go gently into the New Different.

In February, COVID-19 has already eclipsed election news. My adult son in Oregon and daughter in New Jersey are scheduled to fly into Fort Lauderdale on the 25th. It never occurs to me to cancel.

In early March, my good friend Margaret, who is already sheltering-at-home in Massachusetts, calls to find out how I am. My snowbird season ends in a month. I’m scheduled to give a talk in New Jersey in May. Blah, blah, blah…

I rattle on, “…and so I’ve got a flight to New York on April 7. I’ll stay there for Passover, then go back to D.C., and we go to Fire Island in August, so I guess I’ll…”

“Seriously?” Margaret interrupts. She is a strong, smart woman, who doesn’t suffer fools. “You’re making plans as if nothing is happening. You might not be going anywhere!”

After we hang up, she sends me a link to “New York Second Coronavirus Case: Attorney Working Near Grand Central, published on March 6. Reading it, I’m grateful to be in Florida. My New York apartment is blocks from Grand Central. The article also underscores how quickly the virus can spread.

I wash my hands more often and begin to use my elbow to ring for the elevator. But I still travel up and down in that cramped space, 12 flights, six to eight times a day, pup in tow. Almost no one wears a mask in my 419-unit building, including me. I hold my breath and turn my back.

I grasp the severity of the pandemic but through most of March, I feel like I’m in a bubble. Staying home in Miami is not so bad. I have a balcony and a pool and a handful of neighbors — all consequential strangers — whose stories I love to hear. I’ll swim every day to mitigate stress.

On March 22 Miami orders condominium associations to close their pools.

Reality chips away my denial. On April 5, Sue, a close friend, sends me a link to “My Mother Has COVID-19”  I met the author at a memorial service last June and, a few months later, had lunch with the mother, a psychotherapist who is my age. The virus now has a face.

I met the author at a memorial service last June and, a few months later, had lunch with the mother, a psychotherapist who is my age. The virus now has a face.

Today, I wear a mask (and not just because it’s mandatory) whenever I’m out and gloves in any enclosed public space. I shop on Instacart and Amazon. I walk my dog alone.

When I stop for conversation, I stand ten 10 feet away. (A Belgian-Dutch study advises even greater distancing — 4 to 5 meters (13 – 16 feet) — if you’re biking, running, or walking in a line because the other person’s “airstream” might be contaminated.)

I’ve changed my habits over a period of weeks that feel like months. Others do more, some do less. I do what I feel keeps me safe. As I texted a neighbor recently:

Each of us draws her own line in the sand where this virus is concerned.

I try not to lecture the laggards –people who are “very skeptical of change and are the hardest group to bring on board.” But as anyone who knows me would predict: Sometimes, I can’t help myself.

A few days ago, for example, a thirtyish guy in jeans and tank top enters the elevator after me and pushes “4.” He is not  wearing a mask and ignores the sign urging passengers to “avoid speaking.”

wearing a mask and ignores the sign urging passengers to “avoid speaking.”

“So how come your dog doesn’t have a mask?”

He can’t see my deadpan expression, but I hope my tone conveys annoyance. “My dog doesn’t need one.”

I wait until the elevator door opens. “Why aren’t you wearing a mask?”

“I don’t believe in it,” he says as he exits on the fourth floor. “This whole thing is a hoax.”

If you ask others, as I’ve been doing, “When did you truly get it and start changing your behavior?” everyone seems to have a watershed moment (or a series of them) when they see a Before and an After. Now is different from Then.

Pam, a psychiatrist in Boston, notes that her After began on March 11th, when a patient’s mother canceled the daughter’s appointment via email, saying “the family was quarantined” but not why. In a follow-up response a few days later, Pam learns that the mother “was at the Biogen meeting that ushered in Boston as an epicenter of the coronavirus.”

Others recall a surprising decision made solely because of the virus. Andrea pinpoints March 12 as “the day I stopped socializing.” She canceled a long-anticipated dinner with good friends. I, too, shocked myself when I told Barbara, a close college friend, that it’s not a good idea for her to stay with me as planned. “I can’t take the chance.”

This pandemic is like a Rorschach test. We each see something different in it. A Palm Beach seventysomething says it feels like “a vacation.” Her time is her own, free of social obligations; she can “rest.” To a sculptor in Long Island, a woman around the same age who recently lost a lifelong friend to cancer, being sequestered is worst than she could have imagined. Because of the virus, the sculptor could not “sit shiva” for her friend; she grieves alone.

I wonder what the “laggards” see when they stare at the changing shape of the pandemic. I don’t judge them. Indeed, my neighbor recently explained why he didn’t “believe in” wearing a mask:

I wonder what the “laggards” see when they stare at the changing shape of the pandemic. I don’t judge them. Indeed, my neighbor recently explained why he didn’t “believe in” wearing a mask:

You only need a mask if you’re caring for someone who’s sick.

I have to admit, four weeks ago I said the same thing to my friend Pam!

This piece also appears on Medium.

So amazing the power of denial

It really is. But we have to have compassion for people who don’t get it. Some simply can’t believe it’s that bad!

Well put. In conversations I realize the different concerns and their depth held by each individual as well as his/her practices to protect themselves and others while attempting to not lose one’s sanity in the process.

It’s true. This is not a linear process. We can blame some of it on politics — we’d almost like to, because that’s nice and neat. But it’s more complex than that.

My day of reckoning came March 20th when I had to attend an obligatory assembly, where I had to cast a vote in the name of my government. That day,I was gripped with anxiety and fear of contagion. After it was over, I literally ran out, bought groceries and started my quarantine, which became stricter every day. I feel good that on March 10th I let my staff work from home, as I felt responsible for their well-being.

There’s no end in sight yet. I want my loved ones to stay safe and ride out the storm.

Thank you! Although this pandemic is a great equalizer, each story of awareness — and acceptance — is unique.